A cultural glimpse into a pregnancy childbirth session in Mumbai

/By Lina Duncan

It was a hot and muggy July monsoon day, minus the rain, and I was off to share a "preparation for birth" session with a new gathering of women. These women had never attended a pregnancy 'class' in their life. Some of them may have attended school to some level. The Foundation of Mother and Child Health (FMCH) started this project, had previously surveyed the area, focussing on the needs of the community, with an aim to improve the health and quality of life for children there. They looked at dietary issues and sharing cost effective methods of making food to benefit children that are anaemic and malnourished. Other interventions include child spacing, family planning, pregnancy and preparing the women for birth. A large proportion of the FMCH time is spent focusing on exclusive breastfeeding and healthy weaning. I admire the work of the close-knit team and always accept invitations to share my experiences and tips to any pregnant women who express interest in childbirth education.

So I jumped on the local train (with no doors, like in the film “Slumdog Millionaire) with my baby doll, pelvis, placenta, a knitted boob, all stuffed in my backpack. I also carried an illustrated large display book with diagrams of baby in the womb, baby’s growth through trimesters, and what the body does to prepare for birth.

It was not easy to reach the little room where session was to be held, and I asked my guide how the women could even get out to the hospital in the middle of night, as the road went far inside to a dead end place and climbed uphill where it ended. Many families live on the hill in a jumbled puzzle of chaotically placed, simple homes. The bus from the station had been overflowing, we could not get on, and the rickshaws (like Thai tuk tuks) did not want to take us "such a short distance" - I was thinking it was about half an hour walk from the station.

Eventually a rikshaw driver agreed to take us to the start of the road and we walked into the slum. My mind was imagining young women in labour in the middle of the night and the hassle it would be to try to get anywhere near a hospital. These women need to travel to a government hospital in labour which would take a minimum of 20-30 minutes.

In recent years the government have been on a major push to lower maternal and neonatal mortality, institutional births are encouraged. You can read more about this here. An alternative would be to go and birth in the village with a traditional "dai", a midwife who has probably learned her trade from generations past, or from an interest in birth, maybe starting with helping goats, and moving on to humans.

The small room was opened already, and some wide eyed and shy women were eagerly sitting on the floor. As we waited for the late-comers I introduced them to my baby girl doll and took every moment as an opportunity to bring positive truths to them. My doll being the first of these as she is black and unfortunately people prefer fair skin babies, all over Asia. So I affirmed her beauty and her female sex, and spoke to her as if she was my longed for, and loved baby of my own. There is a campaign called "Dark is Beautiful" in India that “seeks to draw attention to the unjust effects of skin colour bias and also celebrates the beauty and diversity of all skin tones”. One very special 7 year old I know washes her face and arms with toothpaste because her classmates tell her she is too dark. Kids pick up all these messages from the TV where skin lighteners are adverstised etc. Even the poorest communities have TVs. It saddens me to see this predjudice and preference for lighter skin colours.

With the last arrivals all squashed in to the small room, I moved on to female anatomy, womb, cord, placenta, amniotic fluid etc and we had fun learning and discussing the words in Hindi. Marathi is the local lingo in the area but I teach in Hindi because I can't speak Marathi and because Hindi is the national language. Women from all places come to settle in urban cities. The woman in charge translated into Marathi. Some mothers brought their daughters and sons, they were refused entry (for lack of space) but I managed to persuade the team that it's healthy and natural for them to be included, especially as they barely get any sex education in school.

We talked about the signs of labour etc, and I could see these bright shiny eyes smiling back at me as they recognised and understood what had happened in their previous births, as I was putting a language to things they had experienced but no one had shared with them. We covered all the possible signs I could think of and then progressed to what happens on admission to hospital and what to expect.

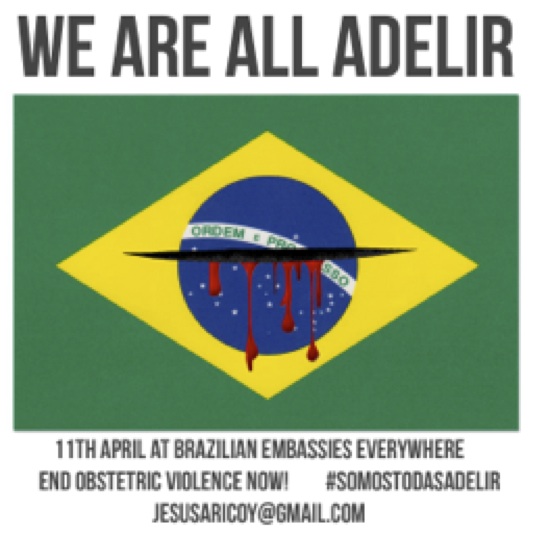

Now this is like walking a tightrope for me. Is it beneficial to know nothing and just float away into a discounted, “shut down zone” when experiencing pitocin for inducing or augmenting labour with no explanation? With no pain relief offered, multiple vaginal exams by more than one care provider, with no explanations or consent? Also, with manual dilation of the cervix, fundal pressure, episiotomy and separation from baby? Probably not beneficial as far as the fear factor goes, whilst lying on a table, not allowed to be mobile, not allowed to eat or drink, and with IV fluids running.

"Masala meds" may be introduced at any time to the iv cannula. "Masalas" in Indian food culture are different, delicious spices mixed together in preparation and whilst cooking, to create amazing food. Masala meds are usually Pitocin, to hurry along the baby, Drocin and Buscopan to relax the cervix and help it to dilate? They are “pushed” / infused in the IV fluids all together, hence the name “Masala Meds”.

I decided that information was better than ignorance, and not wanting to instil fear I passed on to these sweet women some relaxation and comfort tools, something to focus on when things get hard and to look forward to the end result. I also gently explained that they would most probably get an IV, that medicine would inevitably be added to it to speed things up, that they may feel scared and alone but to remember to keep their jaws relaxed and try to relax their bodies and minds inbetween the wave like contractions. I taught them Ina May Gaskin “horse lips” and how to make low sounds quietly so they are not told to shut up. Women have to be brave to enter a government hospital to give birth, so I tried my best to make them into brave birthing warriors and not to fear the process, and I made them laugh a lot too. Laughter is always good.

It makes me sad that these young girls and women need to know about routine episiotomy and fundal pressure, but these practices are common place (and in the most expensive hospitals in town), and there is no such thing as a birth companion, an explanation or a consenting to a procedure. Tasks are performed and babies are extracted, I cannot really describe what I have seen, during birth. The new baby goes away, upside down for a minute, screaming, and comes back with it's genitals, not its face, to meet it’s mother. I showed them this as an example with my doll, and they all had a good laugh. I had tears in my heart and my throat. What a sad way to meet their special little one that grew inside. I have witnessed young girls eyes either light up or shut off according to what their in-laws are hoping for, mostly male babies, although this is slightly and slowly turning around. This makes my heart sing.

Class ended with my baby doll (with cord still attached) naked and covered with a blanket (and no hat) in skin to skin position. I explained the benefits of exclusive breastfeeding and skin to skin and explained that if they want a healthy and thriving baby, then that's what they can do, as much as possible. I talked about delayed cord clamping and the women who had birthed in the village with dais knew exactly what I was talking about. Dais respect the placenta as a life giving organ and even use it as a tool for resuscitation for “slow to get going babies”. They put the placenta into a bowl of warm water and massage it, and usually the baby soon takes it’s first breath, or breathing and colour imporves with this technique. Of course the babies get their own stem cells too which is most beneficial. I told them I am going to write to the priminister Modi so he may change the protocols, and therefore possibly turn around the huge problems of anemia in India.

A couple of them spoke up about their hospital births and one lady shared about her village homebirth. I smiled knowingly at her and she understood what I was conveying in my smile back to her - well done!

I lent my doll to a little boy, for a few minutes whilst everyone ate a banana. He had come with his 7 month pregnant mother. She didn't look more than 4-5 months.

As I left and walked down the road to get back to the train station and my home, I day-dreamed of a small community birthing centre there, where women would be shown kindness, dignity and respect, and where babies would be welcomed in a way that honours new life and enhances bonding and nurturing. Maybe.....

One day.

Let's train an army of midwives for a land that has an astronomical amount of births per year. This land where women need an overdose of kindness and compassion whilst giving birth and beginning motherhood.

Lina Duncan

Lina Duncan lived in Mumbai for 9 years, where she set up a private business providing midwifery services in collaboration with Indian doctors who acknowledged the midwife model of care. In her spare time she volunteered to facilitate local vulnerable women and families to access public health care for all things perinatal and offer support on their journeys. Lina loves to share information and especially enjoyed these classes, run by a local NGO. She is returning briefly to India to speak at the Human Rights in Childbirth conference in Mumbai from 2nd-5th February 2017 (see links below). Follow @HRiCIndia2017 on twitter for pre-conference updates and live tweets from the team.

Human Rights in Childbirth together with Birth India are hosting a conference in Mumbai this 2-5 February. To register click here or here to find out more!