A Passion for Birth: passing on the baton

/My family - 5 girls

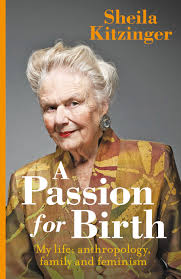

I recently read Sheila Kitzinger’s biography – A Passion for Birth. The first thing that struck me was the synergy between Sheila’s life and mine. It was quite a revelation. Poles apart in terms of heritage and social standing, Sheila and I not only have similar names, but Sheila was born to a strong rebellious mother as I was, she was mother to five girls, and I am the youngest of five girls. Like Sheila, there is no division in my life between work and home – it all blends into one, and childbirth and women’s human rights thread through the core.

Until I read her biography, I wasn’t aware of these aspects of Sheila’s life. The book reveals facts about this legendary woman, who set the scene for radical change in childbirth practice in the UK and around the world, and challenged us to think about the experience of childbirth as a potentially exciting, exhilarating, and fundamentally important event. Sheila's work and passion epitomizes the ROAR of childbirth activism.

During the first part of my career, in the early 1980s, birth activists were mystical beings that I never saw – and inspirational texts were far less accessible. Individuals like Ina May Gaskin and Sheila Kitzinger influenced my thinking, my practice, but their physical presence was far from my life. These inspirational women provided me with ideas for ‘another way’, when I was immersed in a culture where ‘doing to’ women was the norm, and permission was not sought for routine unnecessary medical intervention.

Having been brought up in a family of only girls, gender inequality hadn’t occurred to me, even though my wonderful mother, like most women, did the ‘double shift’ of paid work and unpaid housework and motherhood. Until I read Sheila’s work I didn’t understand the enormity of women’s rights, and how childbirth was fundamental to the struggle. During my early career childbearing women were compliant, and any woman revealing that she’d attended NCT classes was labeled ‘difficult’ even before the next sentence. Midwives conformed to hierarchies too, and bullying was accepted. I remember a time when I was reprimanded by my colleagues for ‘allowing’ a woman to have a bath shortly after giving birth. The midwives were horrified, as it was the usual routine for a woman to have a bed bath shortly before being transferred to the postnatal area. I couldn’t believe it. I’d worked in the GP maternity unit (that was part of the same organisation) for years prior to this, and there it was normal practice for women to soak in a bath immediately after birth. My superiors told me I was practising dangerously. I challenged the directive, and there began my first move to try to influence maternity care, and I contacted other units in search for evidence. I was never confident even though my belief was strong. I was considered rebellious (for such a simple thing) and ‘alternative’. It was around this time that I read Sheila’s book, Pregnancy and Childbirth (1980) – it was a revelation. My instinct to question unnecessary rituals was founded, and looking back, it was then I began to ROAR. With a few like-minded midwives, mostly fellow members of the Association of Radical Midwives we searched for evidence to support change. I was fortunate to work with an enlightened head of midwifery, Pauline Quinn, who listened to feedback about our maternity service from women who had their babies with us, via a local NCT tutor. Clare Harding was a highly educated individual, and a member of the Maternity Services Liaison Committee. Slowly, things began to change. The separation of mothers and babies, binding engorged breasts, giving milk supplements to breast-fed babies, and enemas, pubic shaving, routine episiotomy gradually became activities of the past. But it wasn’t easy, and if it wasn’t for the injection of information and assurance via articles and books from people such as Sheila, I would have been more reticent. The compassion within me that lead me to choose midwifery as a profession, that helped me to try to be courageous, was often tested. Like others, I was often fearful….

Today we have evidence, and greater access to midwifery and obstetric leaders who continue to push boundaries to promote and support women centred care. We can even chat to them via social media channels. Social media also enables us to learn about innovative practice, and can link us with like-minded individuals then we can join together to enable a greater, unified message. However, we also have the increasing fear of recrimination, of litigation and doing the ‘wrong thing’, that is leading to defensive practice and vicious circles of despair and distress. This isn’t resulting in a safer service, quite the opposite. Because of this, and due to our extensive networks, Soo Downe and I decided to bring together a global voice to speak out and identify the need for another way, and to highlight practice where positive change has been made. We wanted to convey the notion of a link between compassion and love as a antidote to fear, and to try to encourage practitioners to acknowledge the difference between real fear that protects us, and manufactured fear that potentially leads us to practice defensively, and adds to an already stressful situation (Dahlen 2010),.

And through the years leading up to the birth of The ROAR Behind the Silence, Sheila’s philosophy has underpinned my actions, my search for courage, and my attempt to spread compassion.

Sheila Kitzinger certainly handed me the baton, and I am always willing to pass it on.

Reference:

Dahlen H (2010) Undone by fear? Deluded by trust? Midwifery 26, 156-162