Normal birth - a moral and ethical imperative

/Updated on the 14th August, 2017

It has been a very troublesome weekend.

Using old news, from one particular source, the UK press have run with a story based on the above press cutting. Same information - except the click-bait used was that midwives were to stop promoting natural childbirth, and the Royal College of Midwives had removed their Campaign for Normal Birth site, and were 'dropping' the use of the term 'normal birth', Right, now I want to make some things clear.

1. The Royal College of Midwives discontinued the Campaign for Normal Birth (CNB) THREE YEARS AGO. I was actually part of that decision, and it was due to the fact that the College felt it was important to encompass antenatal and postnatal care within the initiative, and public health. So 'Better Births' was born. It had nothing to do with the Morecambe Bay Report, which was published after the decision had been made. But even though the 'Campaign' ceased, the support for normal birth has not. The RCM have a normal birth resources page. Some of the resources developed for the CNB have been removed following a request, and will hopefully be replaced with more up to date material. Since writing this post, Cathy Warwick CBE, CEO of the RCM, has written to confirm the College's continued position to support midwives to promote and facilitate normal physiological birth.

2. THERE IS NO EVIDENCE that the RCM's Campaign for Normal Birth had any direct influence on the tragedies that occurred at Morecambe Bay, or any other service. The adverse events at Morecambe Bay were attributed to five elements of dysfunctionality, one of which was the 'over-pursuit of normal birth'. The report does not apportion blame to any one of the five individual elements, but to the whole five. In any case - why is the one element linked to resources supplied by the RCM?

3. I believe in choice, autonomy, and safety. Out of our 9 grandchildren, none have been born 'normally'. They needed expert medical intervention, medical support, and I am eternally grateful for the attention they received. I also understand the evidence that physiological normal birth is the optimal way to give birth for most women, and that most women want it.

4. I hear and fully respect that some women feel that the word 'normal' in relation to birth is divisive, and upsetting, leaving them feeling like they 'failed'. I can understand this, that women may feel disappointed if they wanted a particular birth experience, worked towards that goal, then it didn't happen. But that's it. I would like to suggest that it is the end result is the disappointment, more than the word. Would women feel less disappointed if birth was called physiological? I liken this debate to infant feeding. If a woman has problems and ceases to breastfeed her baby, she feels disappointed - no matter what the term is. Normal birth is a normal physiological bodily process - as is normal respiration, and digestion. The terms physiological, natural and any other are fine too, but let's not blame a word for disappointment. We need to listen to the experiences of women when they are unhappy with their birth experience for whatever reason, then aim to change services so that optimal childbirth is the goal, for a healthy mother and baby. I will not stop using the term 'normal birth' and I will support midwives to facilitate women's choices safely,

The reasons why I say this are in the original blog post, below.

May 2017

Sheena Byrom OBE with Professor Soo Downe OBE

I found the article at the top of this page, and one several days later, particularly disturbing. First of all, the harrowing stories of where a family has lost their baby are beyond shocking for the reader. There are no words to express the intense, life-changing grief those involved are feeling. I must mention the health professionals involved, also. I am fully aware of the trauma for them too. No-one working in health care services goes to work to do harm, and the suffering when mistakes are made is also traumatic and devastating. Yes, there needs to be learning from incidents, and development where needed. But blaming one professional group, or a particular type of birth, does little to improve any situation.

Why does 'normal birth' matter?

A review of all the relevant studies of what matters to women, from around the world, including the UK, has found that: Women want and need a positive pregnancy experience. This includes: maintaining physical and sociocultural normality; maintaining a healthy pregnancy for mother and baby (including preventing and treating risks, illness and death); effective transition to positive labour and birth; and achieving positive motherhood (including maternal self-esteem, competence, autonomy) [Downe S, et al 2016].

The issue here is increasing sensitivity, in the press and among politicians, a few activists, and health care providers, to the word ‘normal’. All these studies made it clear that the vast majority of women want to go through pregnancy, labour, birth, and the postnatal period relying on their own capacity to grow, give birth to, and nurture their babies themselves – ie, in the usually accepted sense of the word, ‘normally’. Indeed, supporting women to achieve this as far as they want and are able to do so, while helping them and their babies to be as healthy as possible, is the fundamental function of ‘midwifery (Lancet Midwifery, 2014).

“the term ‘normal birth’, and all that it relates to, is being rapidly relegated to a rarity in practice...”

However, it seems that the term ‘normal birth’, and all that it relates to, is being rapidly relegated to a rarity in practice, or even (negatively) to cult status among the media and other powerful stakeholders (who are mostly not childbearing women, it should be noted). I regularly spend time with student midwives from around the UK and beyond. They tell me they are worried about practising as qualified midwives, as, during their training, they hardly ever see women who have had a normal, physiological, straightforward pregnancy, labour and birth. This section of a letter the RCM received from a student midwife in 2014, summarizes these concerns.

'However, I became very disheartened and concerned about my own experiences. As a student midwife, I completed my second year of training after having witnessed and participated in 52 caesarean sections, 16 instrumental deliveries and very sadly, only 11 normal deliveries. I can vouch for the fact this story is not unique and many students are having a chronic lack of exposure to normality. In fact what the International Confederation of Midwives and Royal College of Midwives seemed to call 'normal', to me seemed like a fantasy, not the world in which I was training and learning. I was saddened to realise that I'm now a third year student and have never used intermittent auscultation in practice and have never seen a women give birth off her back'. Student Midwife to RCM 2014

The situation remains the same three years on, or potentially worse.

How are student midwives and eventually midwives able to support women to achieve what they want to achieve, AND call for assistance when there is a deviation from the normal, if they have never seen it?

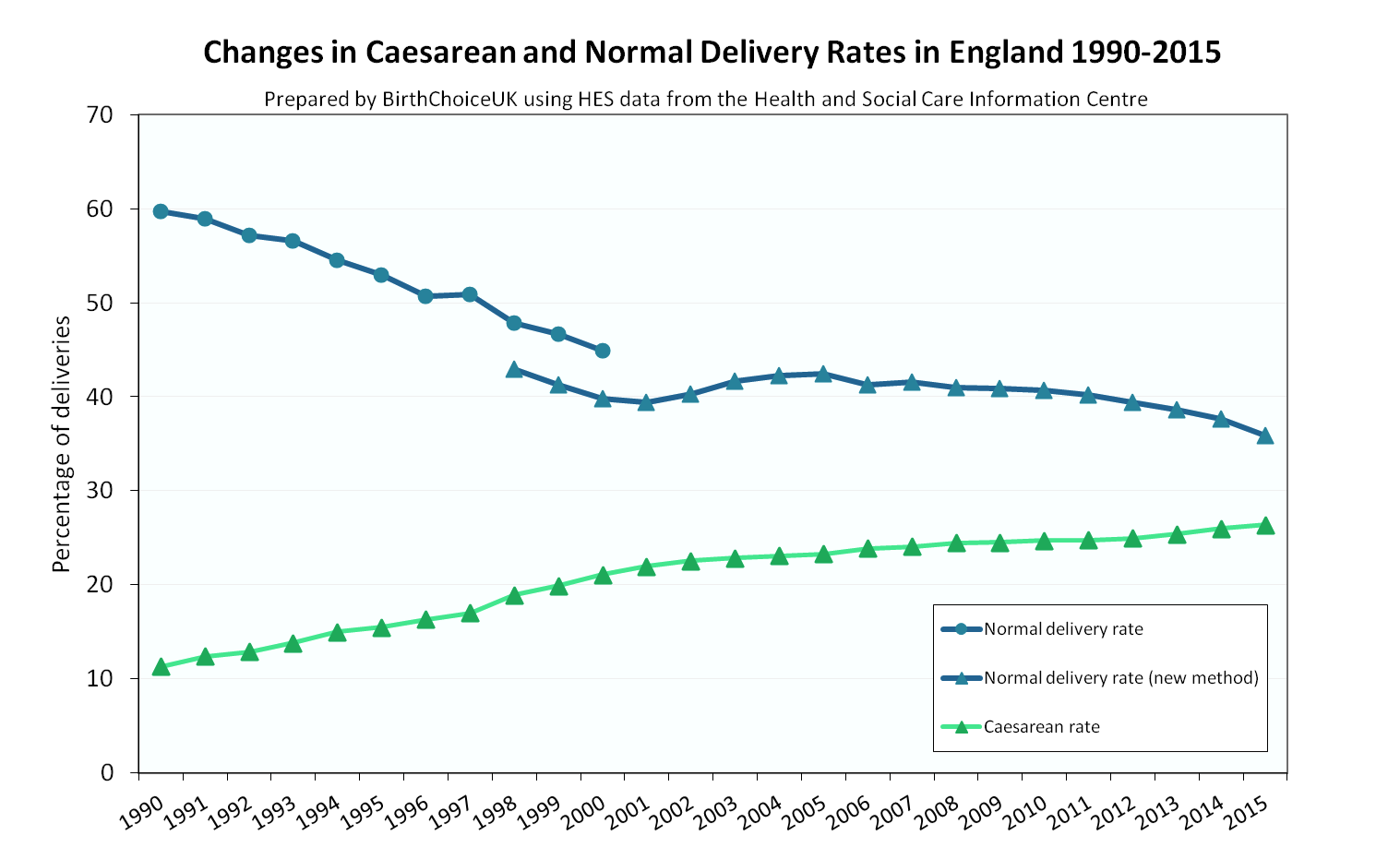

Recent press reports add to the fear already embedded in maternity services. This fear is real in high income countries (Shaw et al 2016), and influences the decisions of women, mothers and families alike. Many maternity units in the UK are being challenged by the Care Quality Commission to increase their normal birth rates, and to reduce their induction and CS rates. If the culture of the organisation is to intervene ‘just in case’ out of fear, and to avoid litigation, recrimination and negative press- how do they achieve these targets? And if there is a widespread problem where midwives 'pursue normal birth at any cost', why are the statistics below so stark? Surely, the opposite would be the case?

“We don’t have a problem talking about normal weight, or normal urination, or normal breathing”

The term ‘normal birth’, and all that it means, has been debated for years. Some have argued for alternative terms, that are seen as less judgmental (though it isn’t clear if women have been asked if they are being judgmental when they talk about their normal birth). These alternatives include terms such as natural, physiological, uncomplicated, or straightforward. However, the term ‘normal birth’ is used by the World Health Organisation and Scotland's recent directive for future maternity and neonatal services. We believe the term will be used by the new digital data collection system that will be set up as part of the implementation of England's Better Births report. It is on the list of terms that the EU think should be used in this context, it is in the title of the international normal birth research conference, (which has been running successfully for 12 years around the world). We don’t have a problem talking about normal weight, or normal urination, or normal breathing. It seems very strange that ‘normal’ childbirth, in contrast, should be so very contentious for some commentators in this area.

WHO says that 80% or more of women should be able to give birth normally around the world (which means more should be able to do so in the UK, given the overall level of health in the UK as a high income country). The fact that only about 35% of women are supported well enough to actually achieve this in the UK (and that many of the remaining 65% feel failures as a consequence) is an indictment of our maternity service provision, and not of women themselves. If we actually were successful in supporting women to achieve the rates of physiological birth that should be possible for them, at the same time as helping the small minority of women for whom this is not possible to feel positive about the interventions that are really needed for themselves and/or their baby, we would not be in the position we are in now, where normal is seen as something exotic that should not be promoted.

There does not seem to be much debate about the move to increase breastfeeding, for the wellbeing of mother and baby in the short and longer term. It does seem strange, then, that there is so much debate about any project to increase rates of normal birth, for the same public health reasons (and, indeed, for reasons of improved mental health, for mother, baby, and family). It seems that we might be being distracted with this debate, when the underlying issues are much more about the continuing undermining of women’s confidence in their bodies and in their ability to grow, give birth to, and mother their babies. Indeed, the pressure, in contrast, seems to be in the opposite direction, as women are increasingly being persuaded to buy in to monitoring, technical intervention, and the need to meet narrow standardised ‘norms’ (that are not physiologically ‘normal’ for them as individuals), which, in turn, makes them more prone to a diagnosis of ‘(potential) abnormality’, which renders them increasingly unable to believe in their own capacity – and so on, in a vicious cycle that actually increases risk for mother and baby.

A moral and ethical imperitive

The debate seems to have become polarized as ‘either a healthy baby OR a normal birth’. The vast majority of women want both. While it is right to ensure that as many women and families have a baby that is healthy, it is equally right to work towards ensuring that as many women and families as possible have a birth that is as physiological as possible. Promoting normal birth while also maximising the wellbeing of mother and baby is therefore not a cult, or a professional project, or a conspiracy. It is a moral and ethical imperative, that should be supported by all of those with any interest in the wellbeing of mothers, babies and families, in the short and longer term. This includes professionals, journalists, politicians, health service managers, childbirth activists, and lawyers.

It is very far past time to turn the tide.

References:

Downe S, Finlayson K, Tunçalp O, Metin Gülmezoglu A 2016 What matters to women: a systematic scoping review to identify the processes and outcomes of antenatal care provision that are important to healthy pregnant women. BJOG. 123(4):529-39

Lancet Midwifery Series (2014)

Shaw et al (2016) Drivers of maternity care in high-income countries: can health systems support woman-centred care? The Lancet Vol 388 No 10057 Available at: http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(16)31527-6/fulltext