3rd-7th June 2013

Well, what a week! It was busy, busy, but it was like being in midwives’ heaven. It's one thing being able to listen to inspirational individuals talking about a topic you are passionate about, and quite another being surrounded by like minded ‘maternity’ people for a whole week! Wow.

And Mary Ross-Davie and I were together for that week, at three different Normal Birth events! So, whilst now missing each other’s company, we decided to write a joint post on our reflections of each event, and to share the pleasure with you all. Hope you find it useful…

The first event was the Royal Society of Medicine, Maternal and Infant Health Normal birth Symposium, in London on the 3rd June 2013.

Congratulations must to go to RCM President Prof Lesley Page, on the organisation of such a stimulating and successful study day!

With more than 300 delegates, the whole day felt alive with passion, inspiration and hope for the future…and it was wonderful to see vibrant, enthusiastic student midwives such as Oli Armshaw, Hana Ruth Abel and Natalie Buschman mingling with midwifery greats such as Caroline Flint and Nicky Leap. These students are our future (and we have so much faith in them!!), and they are hungrily receiving the baton.

The programme was a great mix of speakers sharing research findings, experience from clinical practice and exploring and celebrating normal birth.

Mary Ross-Davie presented her ground breaking PhD research findings. Now I believe Mary’s work has the potential to change midwifery services, and if used, can add strength to influencing staffing levels. Mary's study, SMILI (Supportive Midwifery in Labour Instrument) looked into the nature of midwifery support in labour. The results are powerful yet not surprising, and include evidence that having enough midwives makes a difference to normal birth rates and satisfaction of childbearing women. Mary's thesis can be found here.

Mary said:

When I started my PhD studentship in 2009 I hadn’t imagined that at the end of it the President of the RCM would be inviting me to speak about my study at a Normal Birth symposium alongside Professor Nicky Leap, Professor Cecily Begley and Professor Lisa Kane Low.

Nicky Leap has written widely about the power of midwives’ approaches to pain in shaping women’s experiences: where we talk about ‘pain relief’ rather than talking positively about the pain of labour we can undermine women’s confidence in their own abilities. Nicky encourages midwives to use the phrase ‘Working with Pain’, and pointed delegates to an NCT resource http://www.nct.org.uk/birth/working-pain-labour) . Nicky’s most recent research has reaffirmed the power of listening to women’s words and stories to learn how to provide better care. It also reminded me of the great impact that film can have in getting women’s voices heard. Nicky and the team of researchers from Kings College London, used videos of women talking about their experiences of care in a learning package for staff. Nicky showed a short extract of one of the films and the message from the women was clear: what midwives say and do and how we do it has a huge impact. You can see what Nicky has to say about workshops for maternity workers when working with women who request epidural anaesthesia in labour.

Consultant Obstetrician Amali Lokugamage never fails to silence an audience. Her articulate, sure, yet gentle style is immediately capturing. And Amali is a unique speaker in that she provides delegates with a detailed and understandable insight into the world of medical practitioners. Maternity services frequently fail women and families when collaboration between health professionals is absent, and so often we hear of tensions between midwives and obstetricians. If health professionals understand each other's back stories and perspectives, and the underlying reasoning behind those perspectives, then there is potential for positive relationships to develop and flourish. After having a home birth, Amali is able to draw on both that experience, and her medical training, to help us to consider the best way forward. Amali's book, The Heart in the Womb, is a must read. Really.

To be honest, the third stage of labour has never really captured my imagination as much as other parts of the childbirth journey, but Cecily Begley’s talk, along with seeing Dr David Hutchon at the Mama Conference earlier this year, has changed that. Her research into Third Stage Management has included a Cochrane systematic review and the ‘MEET’ study which explored Irish and New Zealand midwives’ expertise in expectant management of third stage. There is a growing body of work about the impact of early cord clamping and the importance of taking time to get that first hour after the baby is born right. Cecily powerfully argued that physiological management of third stage should be a basic midwifery competency.

Kenny Finlayson from UCLan reported on the feasibility issues of The SHIP Trial (Self Hypnosis for Intrapartum Pain) which is due to be reported on at the end of 2013. We look forward to that.

Kathryn Gutteridge shared some of her philosophy of birth and how she has worked to make this a reality at the new birth centre where she is consultant midwife in Birmingham. She spoke about getting the physical and emotional environment right for women, for them to have the most positive birth experience possible: she and staff at the unit approach the labour and birth as a unique day in a woman’s life much like a wedding day. Imagine if we treated all the families we look after as if we were their wedding planners for the day…

Mary said:

I loved presenting my research alongside these and other great speakers on the day. As a new researcher presenting my findings I have found it so helpful and encouraging to get instant feedback from people after my presentations through Twitter. Research can be quite an arduous and lonely process, peoples’ responses raise my spirits and encourage me to keep going. What people pick out to tweet shows me what messages really come across strongly. You can find comments (Tweets) about Mary’s talk, amongst the others, here!

The next event was UCLan's Normal Birth conference, Grange over Sands 5th-7th June, 2013

‘Getting it right first time: normal birth and the individual, family, and society’

This famous international conference, organised by Professor Soo Downe and her team from UCLan, always attracts researchers, obstetricians, doulas and midwives from all over the world. This year delegates travelled from many countries including New York, Netherlands, Germany, Brazil, Australia and Italy. The conference has a unique atmosphere – a beautiful location where the sun always seems to shine, with a relaxed feel that belies the serious research that is presented.

Jenni Cole gave a keynote address on day one, which focused on Anti-microbial resistance (AMR) and the overuse of antibiotics in neonatal care. It is estimated that between 90 and 99% of antibiotics administered to newborns are unnecessary, costing the NHS as much as £150 million per annum. In August 2012, NICE published Clinical Guideline 149: setting out clear guidance on when antibiotics should be administered and when they can be withheld. Whilst in theory compliance with the guideline should have reduced antibiotic use, there is evidence that doctors and other health care workers are reluctant to change embedded behaviour patterns. Jenni is looking for English Trusts to participate in research into the issue, and wants to be contacted by email here: JenniferC@rusi.org

This year some of the keynote speakers highlighted initiatives aimed at improving normal birth rates in the USA, Brazil and the Sudan. One of the key shared threads between these talks was the need for strong collaboration between midwives and obstetricians, to strengthen normal birth. Dr Nasr Adalla from Sudan, where less than 50% of women give birth with a skilled attendant, spoke about his belief in the right of women to choose a home birth with skilled support. Keynote speaker Maria do Carmo Leal spoke about the challenges faced in Brazil, with only 15% of births assisted by a nurse or midwife and a very high caesarean section rate (overall 45%, though in Rio the rate is 80-90%). A new programme of work there led by obstetricians, midwives and politicians, called ‘Rede Cocogna’ is working to change this and has led to the opening of 42 new birth centres.

So many fascinating insights have come out of the NPEU Birthplace study. Professor Christine McCourt shared some of the qualitative results in her talk. The study confirmed how far we have come from the simplistic midwife v doctor dichotomy in relation to normal birth, highlighting more tensions between midwives working in alongside midwife led units and their midwifery colleagues in consultant led units than between midwives and obstetricians. It made me wonder what we can do to try to lessen these damaging divisions within our profession (answers on a Tweet to me please! ‘@maryrossdavie’).

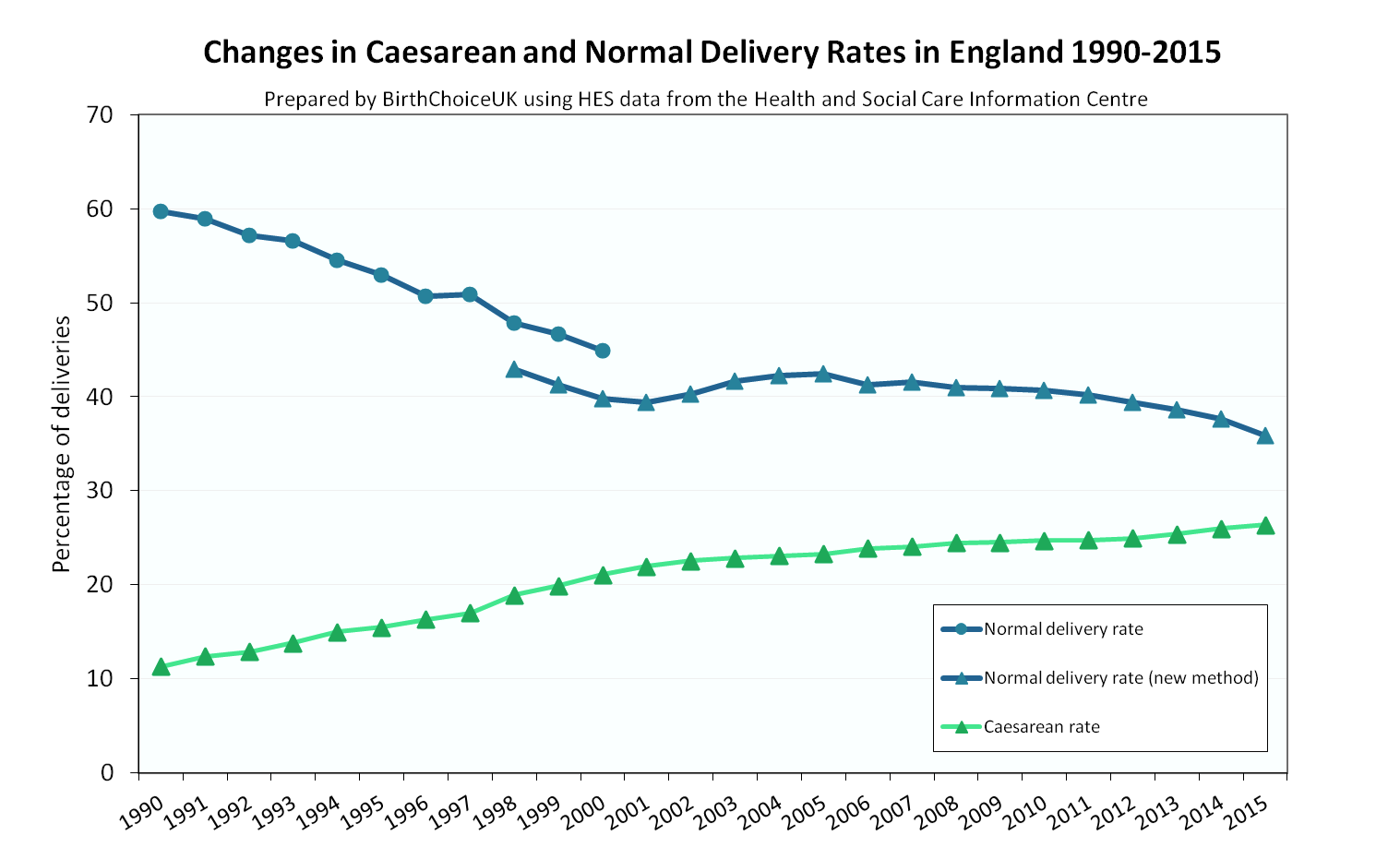

Miranda Dodwell from Birthchoice UK has been working with Prof Jane Sandall’s team at Kings College London. This work has highlighted the huge variations in normal birth rates between NHS trusts in England: ranging from 30-50%. A number of factors appear to make a normal birth less likely for women including being over 30 years old and from the least deprived quintiles. Miranda undertook some really interesting subgroup analysis of the data and found that ‘low risk’ multips had a 75% normal birth rate compared to 15% in ‘high risk’ primiparous women.

Another fascinating source of comparative data is the Europeristat programme of work, presented by Alison MacFarlane, this compares key information about birth processes and outcomes between European countries. Again this raises so many questions for me: why are our stillbirth and neonatal death rates in the UK so much higher than Scandanavian countries? Why did the caesarean section rate in Scotland rise by 3% from 2004-2010, compared to a rise of 1.6% in England? Why are normal birth rates so variable: 42% in Scotland in 2010 compared to 47.2% in England and 50.2% in Finland?

The great thing about this conference (apart from the brilliant people to talk to over the wonderful food) is the sense that you get of a very lively questioning research community that is searching for the answers to how we can make positive normal birth a reality for more women. We didn’t get to see other top speakers: Professor Billie Hunter talking about her work investigating resilience in midwifery and Mary Sheridan on her work exploring vaginal breech.

The next Normal Birth conference is being planned to be in Rio, Brazil in 2014. Now THAT should be one not to miss!

To read more about the conference, see the Twitter feed here, and Consultant Midwife Dr Tracey Cooper has written extensive notes and made them available here Normal Labour and Birth Conf 2013

Believe in Birth Study Day, Montrose, 7th June 2013

Last but not least, Mary and I (and Kathryn Gutteridge too!) were honoured to be invited to the famous Montrose Birth Centre, in Scotland, to speak at their study day ‘Believe in Birth’. When we arrived the sun was still shinning outside and in, that is there was an abundance of smiles and warm welcomes from ALL the staff who work there. Delegates were offered a visit to the Birth Centre in the morning before inspirational leader Phyllis Winters opened the day with enthusiasm and positivity.

There wasn’t a murmur in the room when consultant midwife Kathryn Gutteridge sensitively talked of the effects of child abuse on childbearing women. Kathryn’s words shook us all, and it was clear from the faces of delegates that there was recognition of suffering.

One of the wonderful Birth Centre midwives, Iona Duckett, spoke passionately about her work, building on Mary Ross Davy’s SMILI study, using the ‘TEA’ tool, for emotional assessment in labour. Another special midwife, Jane Wanless, told the story of her midwifery journey. She made us laugh and cry.

Read more about this not to be missed study day here on Twitter!

At the end of the week we felt totally invigorated and enthused to continue with drive to support and protect midwifery and obstetric practice that respects and upholds physiological childbirth. The practitioners who were fortunate to be part of these three amazing events will hopefully be uplifted too, and feel energised to take messages back to their areas of work.

We now need to follow up the suggestion from the RCM's Campaign for Normal Birth steering group (of which we are both members) for a Normal Birth week every year, and also to make events more accessible for maternity workers at all levels.

What are your thoughts on this? Please leave your comments below!