The Lancet Midwifery Series: by a 'Midwife's Midwife'

/At the end of June, and amidst a flurry of excitement and extensive publicity, the much awaited Lancet Midwifery Series was launched. The Series, produced by an international group of academics, clinicians, professional midwives, policymakers and advocates for women and children, is the most critical, wide-reaching examination of midwifery ever conducted. The papers systematically summarise the current global picture of maternal and infant health, and provide a framework for policy makers and maternity providers to maximise potential for improvement.

The Series also highlight key issues on the role of midwifery in the world today, and challenge much of the current thinking and attitudes about it among health professionals and decision makers.

For me, the papers have given us the additional tools to enable and strengthen the drive to lobby for change. The paradox of lack of timely and coordinated life saving interventions in some countries, and over-use of the same interventions in others, needs to end.

Dutch Midwife Petra ten Hoope-Bender , who works as the Director for Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn and Child Health at the Instituto de Cooperación Social INTEGRARE (ICSI) in Barcelona, Spain, co-ordinated The Lancet's Series on Midwifery. I was recently connected to Petra, via Soo Downe, and after reading about her here, felt it would be great to ask her about her role, and about what she hopes her work will achieve.

Hi Petra, thank you for so willingly agreeing to be interviewed for my blog. I know how busy you are! I think many individuals will be very interested to hear about the role you played the development and co-ordination of The Lancet Series on Midwifery, recently published. Would you introduce yourself please, including a little about your professional background?

I'm a midwife by trade and held an independent midwifery practice in Rotterdam for 12 years before moving into the area of international health. I started as Secretary General of the International Confederation of Midwives in 1998 and later I moved to Geneva to start the Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health.

Could you explain briefly what the papers are, why and how they were developed?

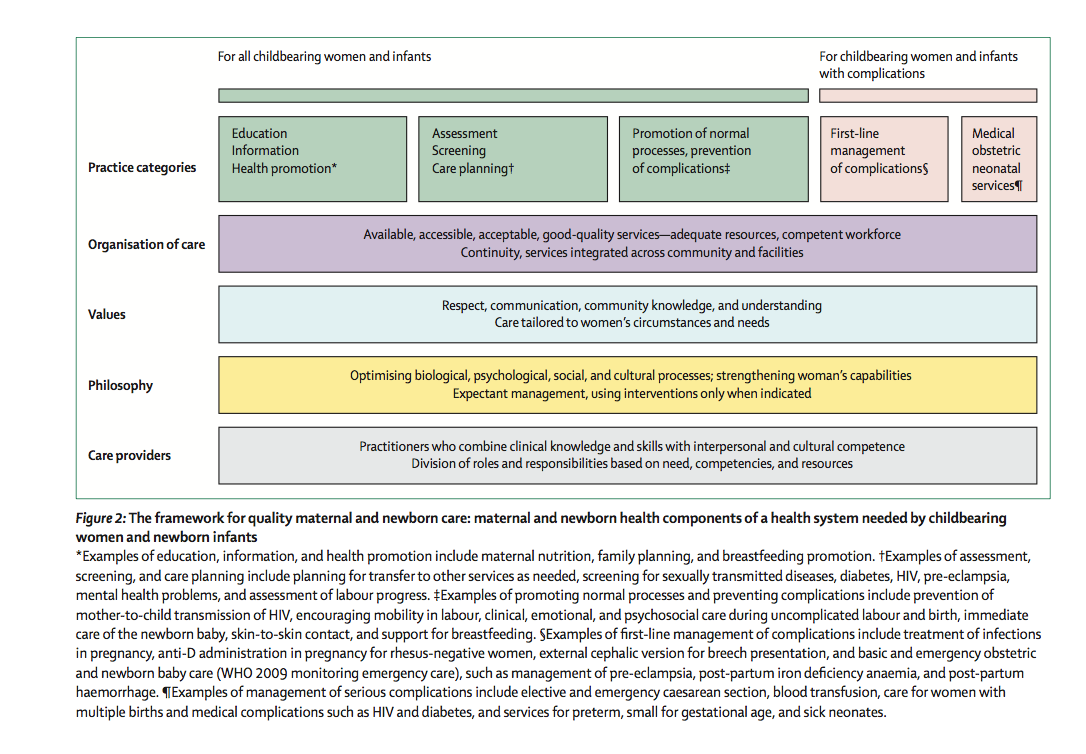

The idea for a series on midwifery started during the development of the State of the World's Midwifery 2011 report, when the author team realised there were many gaps in evidence about midwifery that urgently needed filling. They approached Zoe Mullan and Richard Horton of The Lancet to find out whether they would be interested in publishing this and received a positive response. There were many topics suggested for inclusion in the series, but after several discussions the content settled down around the four topics we have now. These include an evidence base for quality maternal and newborn care from the perspective of women and newborns that expands the notion of what needs to be provided to how and by whom. It sets out an evidence based definition for midwifery and measures the impact of the lives that can be saved by the midwife working to her full competence and scope of practice. The series also identifies the steps that some countries have successfully taken to deploy midwives and thus reduce their maternal and newborn mortality and finally provides an international policy brief that calls for effective coverage (coverage + quality) of midwifery care and shows how this can contribute to the achievement of international targets and initiatives.

What was the extent of your involvement?

I was the coordinator of the series as well as the lead author on ' The improvement of maternal and newborn health through midwifery'. I was also a co-author on two of the other papers in the series.

If midwives or maternity care workers want to influence political agendas using the series, what advice could you offer them?

The first step would be to lay their maternity services against the Framework for Quality Maternal and Newborn Care to see where the differences are and then identify what the most important issues are in their services that they would like to change.

These can be changes in the midwifery curriculum, or in the way the profession is regulated, but they can also be about service delivery and how the care providers are enabled to provide respectful care that optimises normal processes and strengthens women's capabilities to take care of themselves and their families.

What impact do you hope the papers will have? Has there been any influence so far?

The series has already gathered a lot of support and positive responses. We have started a website called Solution98 where we explain for the general public, what the series means and what they can do to support the provision of such quality services in their health system and facilities. There have already been quite a lot of requests for support and even accreditation of facilities to this new standard of care. What I hope most for the future is that women will understand what we're talking about and start demanding this kind of care for themselves and their families, friends, colleagues. Without the voices of women, the effort to improve maternal and newborn care will remain in the realm of the health care providers and will not be half as effective.

What are your plans for the future Petra? In the near future we're working towards inclusion of the messages and the framework from the series on midwifery, to be taken up and linked with the work on reducing maternal and newborn mortality world wide that is currently being pushed by the UN and its partners in large initiatives such as the Every Newborn Action Plan, Ending Preventable Maternal Mortality and the discussions about the post 2015 sustainable development agenda. But this series is not written for low and middle income countries only. It is as important for high income countries where overmedicalisation threatens normal pregnancy and childbirth and where midwifery is under pressure.

Petra, this work gives us hope for the future, and is a pivotal element of the momentum for radical change. Women and their children will benefit as a result of the recommendations, when they are appreciated and implemented. Women and families, together with midwives and all maternity care workers around the world are thankful for the expertise, time and energy you and your esteemed colleagues have given to addressing the issues that they see, hear, feel and suffer from on a daily basis.

And now we must speak out.

Petra's email address is: petra.tenhoope@integrare.es

Find Petra on Twitter at: @Ptenh